Linux is considered a Unix-like operating system which basically means that Linux derives heavy inspiration from Unix without actually conforming to be a full Unix operating system. macOS and FreeBSD would be two more examples of a Unix-like operating system. Again, Linux isn't directly Unix, it's just directly inspired by it, and incorporates a lot of ideas and interfaces into it. Linux was created because at that time there was not a single free open-source re-implementation of the Unix operating system (the BSD kernel was not yet available) so he wrote his own kernel which became known as the Linux kernel. From here the project took off and was adopted far and wide. (At the time of writing) all of the top 500 supercomputers run on Linux, a large share of the mobile market (thanks to Linux being based on Android), and many servers running your favorite websites. Suffice it to say, Linux is very important to the modern computing world.

What you see is often called the REPL, Read Evaluate Print Loop. It's basically a way of interactive programming where you write one line of code at a time, inputting data into and out of small programs. Using the commands here, you can navigate around your computer, read and write data, make network calls, and all sorts of other things. Basically pretty much anything you can do with the desktop you can do with the command line, it's just a little less clear how to do it. The way REPL works is that you send one command at a time and the shell executes the command and returns the result to you. During running that one command, it may print several things. And you can, using some basic programming syntax, write a line that runs multiple times (or, another way of saying "runs multiple times" is looping.)

The first thing we should do is get some terminology out of the way. You are using a shell right now, and that shell is almost certainly called bash (it definitely is unless you changed something), the Bourne Again Shell (which is making fun of the Bourne shell which bash replaced.) It's by far the most common shell and is over 30 years old. There are other shells and we'll talk more about them later, the most common of which are zsh, ash, PowerShell, and cmd.exe. We'll chat about those later. Your shell is running inside some sort of emulator. That emulator could be Terminal.app or iTerm2 if you're on macOS, or it could be the Windows Terminal if you're on Windows 10. This the window that's containing the shell, and you can use that emulator to switch out what shell is running inside of it. For now we want to be on bash (or zsh is basically the same too). A shell is almost certainly called bash (Bourne Again Shell), It's by far the most common shell and is over 30 years old. the most common of which are zsh, ash, PowerShell, and cmd.exe.

The way bash works is that you are always in a folder somewhere on your computer. Our first command we're going to run in your computer is pwd. So type pwd and hit enter. This will send the command pwd to the shell which will evaluate that and print out the answer. pwd is a little program that tells you the current path of where you are in the file system. pwd stands for present working directory. It's basically like asking the computer "where am I right now?". The / represents a level of nesting inside of another folder. The root directory is at /. For most programs, you can try pwd --help and it'll usually spit out some brief instructions of how to use the program.

In the case of cd, we're passing data into cd to tell it how to run. If we run cd .., the .. is an argument or parameter. Not all programs need parameters or sometimes they're optional. Let's look at pwd: it never needs any arguments. Or ls which has optional arguments. If you say ls, it's the same as saying ls .. The . in this case means "this directory". which will tell you the path to where the program you're running is. Arguments are just bits of information you give to a program, frequently they're paths to files or folders but they can often be other things.

--help which is a flag but this commands can take all sorts of flags to customize how they'll act. Like parameters, they're bits of information that change how the command works. Many programs allow you to be lazy and combine flags together. In this case, we can say ls -la and that's the same as ls -a -l (order doesn't matter either.) This is usually true but it depends on the individual command you're running. You can pass parameters to flag too. If we type ls --ignore snap it will not output snap. This can also be written as ls --ignore=snap to make it clearer what that ignore is referring to. We can also say ls -I snap for the shorthand. Lastly if we wanted to do an ls on the /home directory and not show the ubuntu folder, we could type ls --ignore ubuntu /home. In this particular case, the order is important. Immediately after ignore, the part you're trying to ignore is passed, then the last parameters to ls as a whole is passed. This is why some people like that equals. ls --ignore=ubuntu /home is very clear.

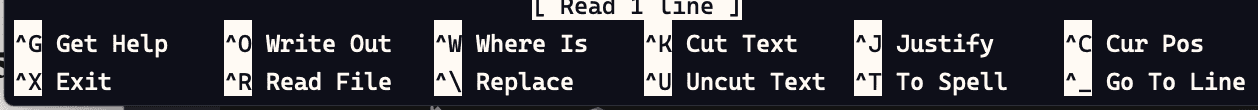

nano is an old open source text editor that itself was an evolution from a previous text editor called pico. Pico was the text editor of the command-line email client Pine that people grew to love so much that they used it for everything. Because Pine was licensed in such a way that Debian wouldn't include it with its distro, Chris Allegretta re-implemented under the name TIP (Tip Isn't Pico, computer scientists love recursive acronyms) it eventually was renamed to nano. Due its tiny size, light weight, and permissive license, nano is included on just about every Linux/Unix-like OS and is frequently the default text editor, even on tiny little embedded devices where even vim is too much. As such, it's a good tool to have your tool belt if you need to do some light text editing.

The genesis of the ideas that went into vim started with an editor called ed (said ee-dee) which itself was inspired by a previous editor called qed. ed was developed by Ken Thompson at Bell Labs in 1969. It is a line-oriented editor and I have no clue how to use it. It's actually rather well known for being pretty user unfriendly. In spite of this, it's still available on most Unix-like systems including Ubuntu and macOS. If you do start it, just know it's CTRL+D a few times to quit it. It's important to note that ed was created in a time where memory was precious, screens were tiny and sometimes just one line at a time, and modems were measured in bits, not even kilobits. It arose at a time when it fit its constraints. vim has multiple modes you can put the editor into. By default we are in command mode. So if you start typing, nothing will appear and you may actually accidentally trigger some commands. If you want to kick the editor into insert mode, just hit i. You should see -- INSERT -- at the bottom to let you know you can type now. I'm going to put vim test. at the bottom of the file. Once I'm done writing and want to head back to command mode, you can hit Esc. You'll see the -- INSERT -- disappear.

Vim has an absolute myriad of commands and I'm not going to get into it. A good example is that here in command mode, you can use H to move the cursor left, j goes down, k goes up, and l goes right (the arrow keys work too but vim masters try to not take their fingers off the home row keys.) If I highlight a character and hit x, it'll delete that character. If I move my cursor to a line and type :d it'll delete the whole line. If I type :d3 it'll delete three lines. There are so, so many and you just have to learn them. If you do desire to go in-depth on vim, you can do one of two things. One is to type :help tutor from the command mode and it'll start the tutor. A more fun way is vim adventures which is a fun game to learn the keys.

A core concept of computing in general is files but in particular when it comes to navigating a command line. In this section we're going to go over some of the core programs you'll want to know so you can interact with files in Linux :

less.lessis a program for reading files.man. it will show manual for a command. If you runman lessit will show you the manual forless.cat.catis short for concatenate because it concatenates the file to the standard output. Similar tolessbut allcatdoes is read the entire file and output it.head/tail. Head will read the first lines of a file and out put them and tail will read the last lines of a file and output them.mkdir. mkdir makes a new directory/folder.touch.touchcreate a new, empty file.rm. Remove a file.cp.cpis short for copy.mv.mvstands for move. This how you move a file from one place to another, or how you rename a file.tar.taris short for tape archive and it initially used to prepare files to be backed up to a magnetic tape archive but it became useful to just group together files in single files as a tarball (like a zip file).

Linux has an interesting concept where basically all input and output (which are text) are actually streams of data/text. Like plumbing pipes where you can connect and disconnect sections to redirect water to different places, so too can you connect and disconnect streams of data. There are three standard streams :

- stdout (said standard output or standard out).

- stdin (said standard input or standard in).

- stderr (said standard error or standard err).

One of the most powerful shell operators is the pipe (|). The pipe takes output from one command and uses it as input for another. And, you're not limited to a single piped command—you can stack them as many times as you like, or until you run out of output or file descriptors.

- User: the owner of the file (person who created the file).

- Group: the group can contain multiple users. Therefore, all users in that group will have the same permissions. It makes things easier than assign permission for every user you want.

Every file and directory in your UNIX/Linux system has following 3 permissions defined for all the 3 owners discussed above.

- Read: This permission give you the authority to open and read a file. Read permission on a directory gives you the ability to lists its content.

- Write: The write permission gives you the authority to modify the contents of a file. The write permission on a directory gives you the authority to add, remove and rename files stored in the directory. Consider a scenario where you have to write permission on file but do not have write permission on the directory where the file is stored. You will be able to modify the file contents. But you will not be able to rename, move or remove the file from the directory.

- Execute: In Windows, an executable program usually has an extension “.exe” and which you can easily run. In Unix/Linux, you cannot run a program unless the execute permission is set. If the execute permission is not set, you might still be able to see/modify the program code(provided read & write permissions are set), but not run it.

In Linux and Unix based systems environment variables are a set of dynamic named values, stored within the system that are used by applications launched in shells or subshells. In simple words, an environment variable is a variable with a name and an associated value.

At all times with Linux a certain amount of processes will be running. A process is any sort of command that's currently running. Go ahead and run ps and see what it outputs. For me the list is pretty short because it's showing just what me, ubuntu, is running which isn't much. ps stands for processes snaphshot. To prove my point, try the following.

sleep 10 &

ps

You'll notice now you'll have a sleep process running as well since you now own that process. So let's dissect a few things here. We'll get to what the & means in a bit (it means run this in the background.) sleep <number> just makes a process that waits for <number> seconds and then exits. So sleep 10 waits for ten seconds and then exits. Every process you run is assigned a process ID which everyone refers to as a pid. Every process is also owned by a user. Some processes will always be owned by root, others by whatever user you are, and others still. If you look at your ps output, you'll those random numbers next to what you're runnning. This is the pid. Sometimes you need to kill an in-flight process. You can do that by using kill and tell it what signal (same signals we were talking about earlier.) Let's try that.

sleep 100 &

ps # find the sleep pid

kill -s SIGKILL <the pid from above>

ps # notice the process has been killed

Note you'll frequently see kill -s SIGKILL as kill -9. They mean the same thing. There are other numbers but I never remember what they are so I just use -s for things like SIGTERM. ps aux will show you everything running from everyone, including all system processes. It should be substantially longer. You'll see a few processes running by you, many from root, and a few from others like systemd+, daemon, and others. This list can be overwhelming so I'll frequently feed this into grep to find things I'm looking for.

ps aux | grep ps

You'll notice the list is pared down to just things have ps in them (including the grep command itself)

A process can either run in the foreground or the background. If something is running in the foreground, you'll see all the output and you will wait until it's finished. If it's running in the background, you can still see the output (unless you redirect it) but you can start doing other things. When you put the & at the end it means "I want this to run in the background" (and hence why we've been using it before.)

Whenever a process exits, it exits with an exit code. This exit code corresponds to if a process successfully completed whatever you told it to do. Sometimes this is a bit misleading because sometime programs are meant to be stopped before they complete (as some like yes will never actually complete by themselves). A program that successfully runs and exits by itself will have an exit code of 0.

date # show current date, runs successfully

echo $? # $? corresponds to the last exit code, in this case 0

yes # hit CTRL+C to stop it

echo $? # you stopped it so it exited with a non-zero code, 130

So what do all the codes mean? Well, it depends on the program and it's not super consistent. It can be any number from 0 to 256. But here are a few good ones that are common

- 0: means it was successful. Anything other than 0 means it failed

- 1: a good general catch-all "there was an error"

- 2: a bash internal error, meaning you or the program tried to use bash in an incorrect way

- 126: Either you don't have permission or the file isn't executable

- 127: Command not found

- 128: The exit command itself had a problem, usually that you provided a non-integer exit code to it

- 130: You ended the program with CTRL+C

- 137: You ended the program with SIGKILL

- 255: Out-of-bounds, you tried to exit with a code larger than 255

Sometimes you need to invoke a command within a command. Luckily bash has you covered here with the ability to run subcommands.

echo I think $(whoami) is a very cool user # I think ubuntu is very cool

The $() allows you to put bash commands inside of it that then you can use that output as part of an input to another command. In this case, we're using whoami to get your username to echo that affirming message out. Let's a more practical one. Let's say you wanted to make a job that you could run every day to output what your current uptime was. You could run this command

echo $(date +%x) – $(uptime) >> log.txt

The +%x part is just saying what date of format you want, and I got that from reading date --help. So end printing something like

06/17/20 – 21:38:34 up 8:51, 1 user, load average: 0.00, 0.00, 0.00

There are far more useful logs to write but you can see here the power of subcommands. Note you can also use backticks instead of $() but it's preferred to use the $() notation. Notably, you nest infinitely with $().

One of the most key things you need to take away from this workshop is how to remotely connect to a server and run commands on it. This is one of the times you absolutely must know your way around bash or you'll be out of look because there's no other way how to do it. One of the easiest things to do is to get a VM (virtual machine) up and running in the cloud. So many companies offer this like Azure, DigitalOcean, AWS, Linode, etc. A VM is literally just a Linux machine running somewhere in the cloud. Many times the only real way to administrate and run code on these servers is just to connect into a remote CLI session and run the code yourself.

The next thing we need to do is to create ssh keys for primary. The ssh key on primary is how it's going to identify itself to secondary. I'm not going to explain how ssh keys work (it's a lot of complicated math) but the basic gist is this: when you generate a new ssh key, you get two files, a public key and a private key. The public key is what you give to everyone else and is not a secret. You're basically giving them a key hole and telling them to install it on a door for you. The private key is just that, your private key. You will never reveal this key to anyone. If anyone does get ahold of this key they can freely masquerade as you. This is the key to the key hole. If you do accidentally reveal your private key ever, you should immediately stop using it and make a new one, to generate public key, Run this:

ssh-keygen -t rsa

# hit enter to put the key files in the default place

# hit enter to give an empty passphrase

# hit enter again to confirm

If you run ls ~/.ssh you'll at least see idrsa (your private key) and idrsa.pub (your public key.) These are ready to go to be used. We're going to use these allow ubuntu@primary to connect to brian@secondary. Run cat ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub and copy the output onto your clipboard.

Change now to your secondary machine.

su brian

mkdir ~/.ssh

vi ~/.ssh/authorized_keys # paste in copied ssh id_rsa.pub from primary, write, and quit

chmod 700 ~/.ssh

chmod 600 ~/.ssh/authorized_keys

Lastly, we're going to need to give ssh an address to connect to. Just like you need an address to mail a letter to, you need an IP address to tell your computer where to connect to. Let's go grab that. Run the command ifconfig. This is going to dump out a bunch of addresses and hashes.

You're looking for numbers like look this: X.X.X.X.

For sure one of them will be 127.0.0.1. That's not it. That's called the loopback: a network address that refers to the same machine. Connecting to that would be like mailing a letter to yourself. Try ping 127.0.0.1. This will send little packets of data to that address and see if it responds. It'd be like looking in a mirror and saying "hey you there?"

Ignore the mask and broadcast. Look for an inet one that looks like 192.168.64.3 or close to it. That's the one you're looking for. That's what the address of this secondary machine to broader network (in this case, this network is just local to your computer.) If you want to make sure it works, try ping 192.168.64.3 and see if it responds with data. If it says it's unreachable you picked the wrong one.

Okay! Now we're ready to connect from primary. Head back there and type this:

ssh brian@<the ip address you just got from ifconfig on the other machine>

You should connect!

Sometimes you need to transfer files between two computers. This can take the form of either transferring files from you local computer to your remote server or from your remote computer back to your local computer. Before we had more mature continuous deployment tools like Azure Pipelines, Travis CI, or GitHub Actions, we often used a tool called ftp (file transfer protocol). While it worked and it was a relatively simple and straightforward of doing things, we moved onto to more reliable tools. However ftp evolved into secure ftp.

using the VMs we set up in the previous section, let's sftp into secondary from primary. The sftp interactive shell is similar to a less friendly and stripped down version of bash. The thing to keep in mind is you're in two directories at the same time as opposed to normal bash when you're just in one. With sftp, you have a local context and a remote context. In order to run a local command, tack an l to the start of whatever command you're running, like lls, lpwd, or lcd. When you want to do it on the remote machine, just run the commands like normal, like ls, pwd, or cd.

sftp brian@<the same ip from the previous step>

lpwd # ubuntu's local home directory

pwd # brian's remote home directory

lls # the list of files in ubuntu's home directory

ls # the list of files in brian's home directory

help # see all the commands you can do

The two key commands you need to know here are get and put. It's from the perspective of your local computer so in this case we're connecting from primary to secondary, so getting something will download it from secondary and putting someting will upload it. This is a great thing to use with tar as well so you can bundle up packages of files before sending them to a different computer.

So now we want to upload a file. Just prefix it with ! and you can quickly run a touch or a tar.

!touch file-to-put.txt

if you need to just disconnect and then reconnect later, but it's helpful for quick things you need to do.

put file-to-put.txt putted-file.txt # second argument is optional, if you omit it'll just use the same name

get putted-file.txt gotten-file.txt # same thing, second one is optional

The two most common tools to do that are wget and curl. Both of these are common to find in use so I'll take the time to show you both but they do relatively do the same thing. In general I'd suggest you stick to using curl; it's a more powerful tool that can do (almost) everything wget can. wget works like cp but instead of copying a local file you're copying something off the net. So you'll identify a remote file (usually a URL) that you want to fetch and save to your local file system.

example of wget :

wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/btholt/bash2048/master/bash2048.sh

chmod 700 bash2048.sh

. bash2048.sh

That wget gets the file, the chmod 700 makes the file executable, readable, and writable for the current user (and no one else) and the . bash2048.sh executes the game. Pretty cool, right? Very cool project. Feel free to play for a second. When you're done, hit CTRL+C to exit. It does exit the shell entirely so may need to open a new shell after via Multipass.

wget can do a lot more than this, including be able to post and various other ways of shaping requests. Just say wget --help to see the myriad options available to you.

While wget works more like cp, curl works more like a normal Linux program. It works more like cat where it operates on input and output streams. Because of this it is a more useful tool to have in your arsenal because you can plug it into other programs.

One last note here, a lot of tutorials or installation of tools will have you do a request of curl <url> | bash. This will nab the contents of the URL off the network and pipe that directly into bash which will execute what's in the contents of the network request. This should make you uncomfortable. You're basically giving whoever controls that URL unlimited access to your computer. But hey! It's really convenient too: you just get and execute the file instantly.

There's a few things to keep in mind when you do it.

- Always read the script you're about to invoke. You know enough now to see notice anything fishy. Be especially suspicious of them making more network requests or decoding base64 strings

- Only do it from domains you trust. It's actually possible to detect a curl request as opposed to a browser request, meaning you can load the file in a browser and see something and then when you go to curl it they can serve you a different file. Basically means I only will do

curl | bashfrom GitHub. - When in doubt just

curl url > file.shand then read the file. From there,chmod 700 file.shand. file.sh. It's not that many more steps.

Ubuntu by itself is a very useful system but we begin to see its infinite possibilites when we dive into the packages that are available to it. Ubuntu comes with its own lovely package manager tools and I'm going to show you how to use some of them to get more tools so you can do more cool stuff.

We'll be going over specifically what Ubuntu has for package management but just be aware that each Linux distro has its own package management tools.

- Debian has dpkg. Because Ubuntu is based on Debian it also has dpkg installed and available to use.

- APT (advanced packaging tool) is based on dpkg and available to all in the Debian family of distros

- Red Hat had RPM, Red Hat Package Manager

- Similar to how APT is on top of dpkg, YUM is on top of RPM to make it easier to use. DNF is the next generation of YUM

- Arch has Pacman

- Alpine has APK Even macOS has one with Homebrew and Windows with its new winget system. Again, we'll be focusing on APT and Snap today.

The first tool of interest is APT, advanced packaging tool. apt is a tool that allows you to download new packages via apt install. Let's just nab one now for fun. Run sudo apt install lolcat. This will go out and fetch the package lolcat from the apt registry and install. After a second it should download and be immediately be available for use. Now try this: ls -lsah | lolcat. You do need to install packages as root.

another example :

node -e "console.log('hi')" # this will fail, Node.js is not installed

apt search nodejs

apt show nodejs

sudo apt install nodejs

node -e "console.log('hi')"

and a few more commands for you to know :

sudo apt autoremove # will remove unused dependencies

sudo apt update # updates the list of available packages apt uses

apt list # everything installed

apt list --upgradable # everything with an update available

sudo apt upgrade # updates all your packages to their latest available versions

sudo apt full-upgrade # basically autoremove and upgrade together

it's just another way of packaging an app up and for the most part you don't really have to care. There's a few things that you do need to keep in mind however:

- Snaps update automatically and you actually can't stop that from happening really. Debs update whenever you choose to do so

- Snaps are safer. They're sandboxed and cannot break out of their home folders. Debs really can do whatever they want

- Snaps are also how Ubuntu lets publish GUI apps like Visual Studio Code, Spotify, Firefox, etc. There's more than just command line tools. [See here for the store][store].

- Debs are reviewed before they're allowed onto the registry. They have to be or else renegade devs could publish anything they want. Snaps, due to their sandboxing, don't have to be.

Much of the same functionality of apt works the same with snap

snap help

sudo apt remove lolcat

sudo snap install lolcat

ls -lsah lolcat

sudo apt remove nodejs

snap info node

sudo snap install --channel=14/stable --classic node

# restart your shell by exiting and starting a new shell

node -e "console.log('hi')"