The Qiskit code in this repository is now depreciated. For an up-to-date implementation of the Shor's algorithm, check out This repository

During the past decade, considerable progress has been achieved regarding the development of quantum computers, and a breakthrough in this field will have massive application particularily in research, cryptography and logistic. Google and IBM recently claimed the creation of a 72 and 50 qubit quantum chips respectively, making the possibility for a potential imminent quantum supremacy even more likely. [1]

In May 2016, IBM launched Quantum Experience (QX), which enables anyone to easily connect to its 5qubit quantum processors via the IBM Cloud. (https://www.research.ibm.com/ibm-q/). Along with it's platform, IBM also developped QISKit, a Python library for the Quantum Experience API, where users can more easily apply quantum gates to run complex quantum algorithms and experiments.

This repository is an introdution to quantum computing and contains the source code to run simples quantum algorithms. They are implemented with the python library QISKit, that can be easily installed with the command $ pip install qiskit (Python 3.5 is required). More information is available at https://qiskit.org/.

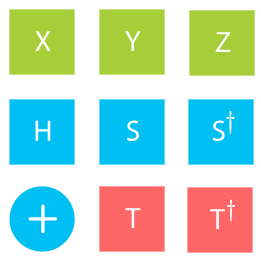

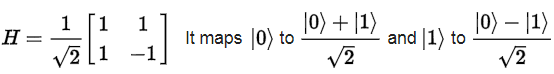

In analogy with the classical gates NOT, AND, OR, ... that are the building blocks for classical circuits, there are quantum gates that perform basic operations on qubits. The most common quantum gates are summarized here --> https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_logic_gate.

For example, the Hadamard gate, H, performs the following operartion:

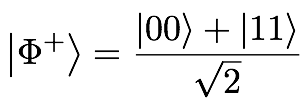

The following code, available in the src folder, create a Bell state and measure it 1000 times.

from qiskit import QuantumProgram

qp = QuantumProgram()

qr = qp.create_quantum_register('qr',2) #Initialize 2 qubits to perform operations

cr = qp.create_classical_register('qc',2) #Initialize 2 classical bits to store the measurements

qc = qp.create_circuit('Bell',[qr],[cr])

qc.h(qr[0]) #Apply Hadamar gate

qc.cx(qr[0], qr[1]) #Apply CNOT gate

qc.measure(qr[0], cr[0]) #Measure qubit 0 and store the result in bit 0

qc.measure(qr[1], cr[1]) #Measure qubit 1 and store the result in bit 1

result = qp.execute('Bell', shots=1000) #Compile and run the Quantum Program 1000 times

print(result.get_counts('Bell'))A possible result that we get is

{'11': 494, '00': 506}

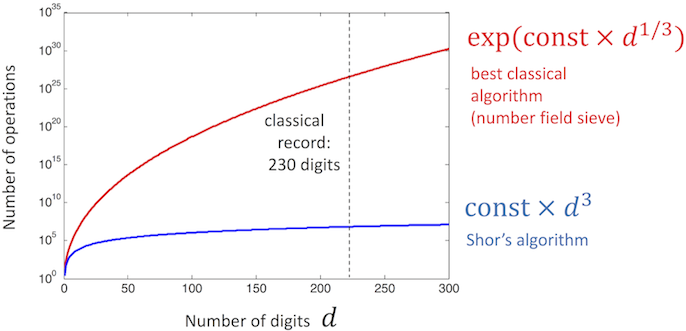

The Shor's algorithm, proposed by Peter Shor in 1995 [2], is today one of the most famous quantum algorithm; it is considerably significant because, while the security of our online transactions rests on the assumption that factoring integers with a thousand or more digits is practically impossible, the algorithm enables to find 2 factors of a number in polynomial time with its number of digits. Shor's algorithm was first experimentally demonstrated in 2001 by a group at IBM, which factored 15 into 3 and 5, using a quantum computer of 7 qubits [3].

Let N be the number to be factorized, and d~log2(N) its number of digit. The most efficient classical factoring algorithm currently known is the [General number field sieve](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_number_field_sieve), which has an exponential asymptotic runtime to the number of digits : O(exp(d^1/3)). On the other hand, Shor’s factoring algorithm has an asymptotic runtime polynomial in d : O(d^3).

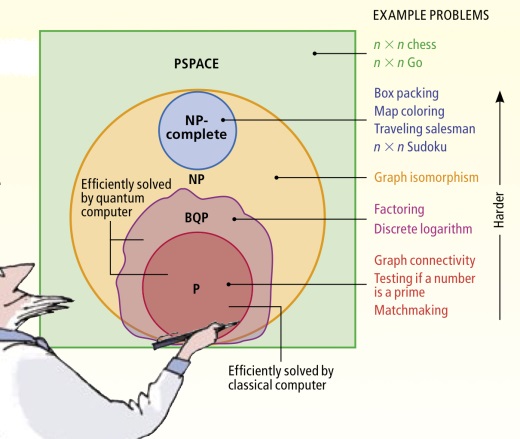

This remarquable difference between polynomial and exponential runtime scaling currently places the Factoring problem into the BQP\P decision class (cf. figure in introduction).

We want to find two factors p1 and p2 that divide N. Before diving into the algorithm, we have to make sure that:

- N is odd (if it's even, then 2 is a trivial factor)

- N is not the power of a prime

from math import log

def Check(N):

if N % 2 == 0:

print ("2 is a trivial factor")

return False

for k in range(2,int(log(N,2))): #log2(N)

if (pow(N,(1/k)).is_integer():

print ("N =", pow(N,(1/k)), "^", k)

return False

return True

With some Arithmetic, Group theory, Euler's Theorem and Bézout's identity, it is possible to reduce the factorization problem into a period finding problem of the modular exponential function (see this page for more details). The classical part of the algorithm is implemented as follow:

from random import randint

def Shor(N):

while True:

#1) pick a random number a<N

a = randint(1, N-1)

#2) check for the GCD(a,N)

p = gcd(a,N)

if p != 1: # We found a nontrivial factor

p1 = p

p2 = N/p

break

#3) Compute the periode r

r = quantum_period(a,N) #Quantum part of the algorithm

if r % 2 == 0 :

if a**(r/2) % N != -1: #If r is a goof period, we found prime factors

p1 = gcd(a**(r/2)-1,N)

p2 = gcd(a**(r/2)+1,N)

break

print ("N =", p1, "*", p2)

return p1, p2

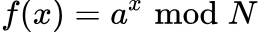

We want to find r the period of the modular exponentiation function  , which is the smallest positive integer for which

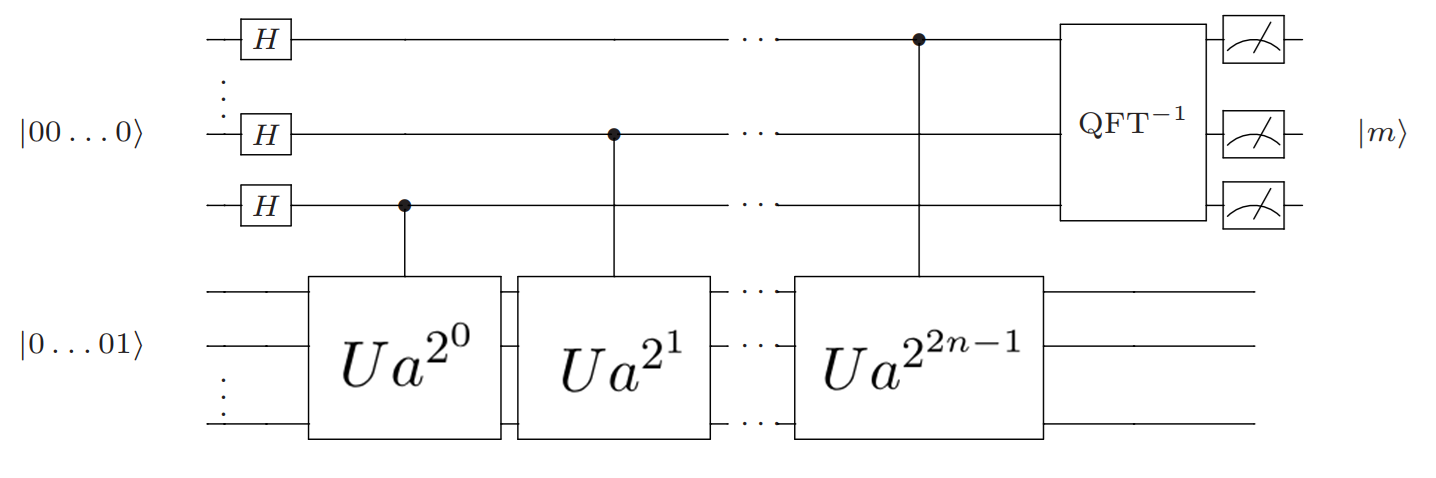

, which is the smallest positive integer for which  . Given the numbers N and a, the period finding subroutine of the modular exponentiation function proposed by Shor proceed as follow:

. Given the numbers N and a, the period finding subroutine of the modular exponentiation function proposed by Shor proceed as follow:

- Initialize n0 qubit and store N in the input register (n0 ~ log2(N) )

- Initialize n qubit for the output register (where 2^n ~ N^2 => n ~ 2n0)

- Apply Hadamard Gate to all of the qubit in the output register

- Apply the controled modular exponentiation gates Ua, Ua^2, Ua^4, Ua^8, .., Ua^(2^(2n-1)) to the input register

- Apply the inverse QFT (Quantum Fourier Transform) to the output register

- Measure the output y

- Calculate the irreducible form of y/N and extract the denominator r

- Check if r is a period, if not, check multiples of r

- If period not found, try again from the beginning

The quantum gate Ua refers to the unitary operator that perform the modular exponentiation function x → a^x (modN). The implementation of controlled Ua as well as the inverse QFT gate are relatively complex [4,5], and the "right" gate set to use is currently still an open question (plus it also depends the architecture used for the quantum computer). Details about how and why this algorithm works can be found in the IBM User Guide.

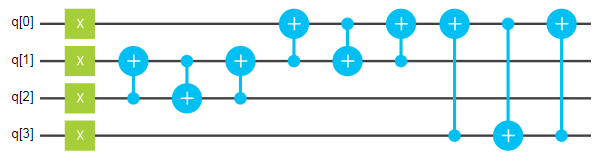

Because the implementation of controlled modular exponentiation and inverse QFT are too difficult in the general case, only a particular case is implemented as a proof of concept, and the period finding subroutne is coded for N=15 and a = 7. The non controlled gate U7 can be implemented as follow [4]:

The simplified subroutine is then carried on by successively applying modular exponentiation until the period is found:

- Pick a ransom number s between 1 and N-1

- Decompose s into binary units and store s in the input register

- Apply the modular exponentiation gate successively until the output match with s

- The period r is the number of time Ua has been applied

Statrting at

s = 3 = [True True False False False]

"11000"

"01000"

"10000"

"01100"

"11000"

Found period r = 4Although this implementation does not use the properties of quantum computers to find r in polynomial time, it is a proof of concept of the modular exponentiation quantum implementation. The code can be found in src/Shor_simplified.

[1]: Kelly, J. (2018). Engineering superconducting qubit arrays for Quantum Supremacy. Bulletin of the American Physical Society. [http://meetings.aps.org/Meeting/MAR18/Session/A33.1]

[2]: Shor, P. W. (1999). Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer. SIAM review, 41(2), 303-332. [https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9508027]

[3]: Vandersypen, L. M., Steffen, M., Breyta, G., Yannoni, C. S., Sherwood, M. H., & Chuang, I. L. (2001). Experimental realization of Shor's quantum factoring algorithm using nuclear magnetic resonance. Nature, 414(6866), 883. [https://www.nature.com/articles/414883a]

[4]: Markov, I. L., & Saeedi, M. (2012). Constant-optimized quantum circuits for modular multiplication and exponentiation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1202.6614. [https://arxiv.org/abs/1202.6614]

[5]: Draper, T. G. (2000). Addition on a quantum computer. arXiv preprint quant-ph/0008033. [https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0008033}