If you're new to assembly, it's worth going through the guide first before exploring this section. The 6502 was developed by MOS Technology and it powered a number of computers like the Apple 2 and Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). It was released significantly cheaper than its competitors (back in 1975) and has helped drive the computer evolution. Although you don't need to learn 6502 to code, it is pretty cool to see what happens "under the hood". If you want to, you can even write games for the NES!

I also highly recommend taking some time to go through the Easy 6502 Guide by @skilldrick. It took me about 6 hours to complete all the exercises and understand the concepts, but you can definitely go through it in less time.

- An Overview of the 6502 Processor

- Common Instructions Explained

- Setting Up Your Development Environment

- Resources

Assembly languages vary depending on the kind of CPU you're communicating with. Assembly is only one layer above machine code, the language that computers can understand, and that machine code changes depending on the CPU. So certain assembly instructions are only understandable by certain types of CPUs.

The 6502 assembly language is used to program the 6502 processor (can you guess where the assembly language it got its name from?). The 6502 processor is an 8-bit processor which means that it deals with data 8 bits at a time.

The 6502 processor has 6 registers, three for general programming use (Register A, X, and Y) and three with specific purposes (program counter, stack pointer, and processor status). We as programmers only have access to registers A, X, and Y, and they can each store one 8-bit number.

We also have access to memory, or RAM. Memory addresses are 16 bits long. But, as we mentioned previously, the 6502 processor is an 8-bit processor. Uh oh! What can we do?

Well first, when talking about register data, we must remember that computers only understand numbers, usually represented by binary digits. When writing assembly language, we can also use hex numbers, which can be a little easier to read.

This is important because later when you look at code examples, you'll see that data is written with only 2 digit hex numbers like $02.

So, if we want to store anything above 8 bits in a register or in memory, we need to use multiple locations. For example, memory addresses are 16-bits long. If we want to store a memory address, we would store it in two consecutive memory locations (eg. $0102 and $0103). That being said, the program counter is an exception, as it can store 16-bit numbers.

For example, a 16-bit value #$1011 at address $1000 would be stored like this:

Address Data

$1000 #$10 ;since #$10 is smaller than #$11

$1001 #$11

Before we get into the nitty gritty of 6502, here's a few things you should know:

- When coding in 6502 (and other assembly languages), we're only doing two things: adding data or modifying it.

- An instruction has two parts: operation and argument. You can think of each as answering the questions "what to do" and "who to do it to". For example with

lda #$00,ldais the operation (also known as opcode, remember this!) and#$00is the argument. In this case,ldameans load whatever the argument is to registerA. So when executed, this instruction will load#$00(which is also just 0) in registerA. - Anything starting with

$like$00is in hexadecimal format - Anything prefixed with

#like#$00is a literal number value while others refer to a memory location in RAM

The 6502 processor has over 50 instructions that are either arithmetic in nature (plus and minus), logical in nature (comparing for true or false), or move the data. Here are some common ones:

| Instruction | Description |

|---|---|

| LDX | Adding argument to Register X (LDA would go to Register A and LDY for Register Y) |

| STX * | Store data at Register X to memory address * (STY for Y and STA for A) |

| CPX | Compare argument with data in Register X (CPY for Y and CMP for A) |

| INC | Increment argument by 1 (INX and INY increment Register X and Y by 1) |

| DNC | Decrement argument by 1 (DNX and DNY decrement Register X and Y by 1) |

| BNE | Branch on not equal (zero flag is set at 0) |

| BEQ | Branch on equal (zero flag is set at 1) |

| JMP * | Jump to memory address * by setting program counter |

Check out the full instruction set!

Arguments can be a numerical number or a memory address.

The processor status register is a special register that tells the CPU something very specific about the current state. It does this by way of setting flags to either 1 or 0. For example, when the Z-flag is set to 1, it indicates that the operation that set the flag produced 0, which is very important for comparison instructions such as CMP.Find out more about flags here.

Before heading into this section, you might be interested in checking out the guide on writing instructions

In the section above, I wrote this:

When coding in 6502 (and other assembly languages), what we're doing is one of two things, adding data or modifying it. So with each instruction you write (like lda #$00) you are just changing the data stored.

To do the above, you need to employ registers which you can think of as variables. As mentioned, the 6502 processor only has 3 registers that you (and I) can access: Register A, X, and Y. To access these registers, we can use the instructions LDA, LDX, and LDY, respectively. For example:

LDA #$00

Loads the number 0 into Register A

Here's another example,

LDY #$0f

What do you think this does?

Loads the number $0f(=15) into Register Y

A small note: Register A is also known as the accumulator so some instructions can only be done with Register A as it is its general purpose. Being able to load values to registers is no use if you cannot use that data later on (just like how setting a variable would be useless if you don't use that variable later on). A few basic actions include:

Addition

ADC #$02

Adds the number $02(=2) to the value at Register A. Note: This instruction can only be performed to data in Register A, not Register X or Y.

Subtraction

SBC #$01

What do you think this does?

Subtracts the number $01(=1) from value in Register A. Note: This instruction can only be performed to data in Register A, not Register X or Y.

Comparison

CMP #$01

Checks whether the value in Register A is equals to $01(=1). If it is, it sets the Z-flag to one (or true).

The comparison instruction also works with Registers X and Y, can you guess how?

CPX and CPY

Once we're done with the data, we want to place it back in the RAM where there is A LOT more space (compared to only 3 registers). We can do this with the store instruction.

STA $00

Loads value at Register A to memory location $00(=0)

An example with Register X:

STX $01

What do you think this does?

Loads value at Register X to memory location $01(=1)

Note: Besides loading numbers into registers, you can also load characters (through ASCII Numbers) and pointers to other memory locations through only writing the hex (eg $02) without the # (which tells the processor it needs to be taken literally).

Speaking of pointing to other locations in memory, in 6502 assembly language, there are a few ways to accomplish this task.

Absolute Addresses

This is the most straight forward method: the memory location (which is a 16-bit number) is fully written

LDA $0001

Load value at memory location 1 to Register A

Here's another example:

LDY $0010

What do you think this does?

Load value at memory location $0010(=16) to Register Y

Zero Page Addresses

When using zero page addresses, the processor assumes that you only want to access the first 256 memory addresses by pre-fixing 00 to the memory address so

LDX $01 === LDX $0001

Load value at memory location $0001(=1) to Register X

Here's another example:

LDA $04

What do you think this does?

LDA $04 === LDA $0004

Load value at memory location $0004(=4) to Register A

Variables

Here, the addresses include a variable which can change. If this was written in Javascript, it migth look something like this:

let x = 1

let a = 0 + x

Here, we set variable x to 1 then set a to the value of 0 plus variable x. a = 1 (NOTE: NOT SUPER HAPPPY WITH JS EXAMPLE, ANY IDEAS?)

In 6502:

LDX #$01

LDA $0000,X

In this instance, we first loaded $01(=1) to Register X then we loaded the value at memory address ($0000 + $01) $0001(=1) to Register A.

In cases like these, we can easily change the value of X (at Register X) so you can also think of the memory address $0000 as the relative base and the value of X as referring to X memory address from the base. So where X = 3, we'll be discussing the location at 3 memory addresses after $0000.

Here's another example,

LDX #$04

LDA $0000,X

What do you think this does?

Load number $04(=4) to Register X then load value at memory address $0004 ($0000 + $04) to Register A.

Indirect Addressing

Indirect addressing is when you use an absolute address to look up another absolute address. JMP in the only instruction that uses this addressing mode. Whatever number is retrieved becomes the absolute address used. Here's an example:

At memory location $0010 there is the value #$01 and at memory location $0011there is the value #$02.

JMP ($0010)

At the end of the example, we are jumping to memory location $0102

In this instance, we do 2 things:

- Retrive the data at memory location $0010. However, instead of only retrieving data at memory location $0010, we also want to retrieve data at memory location $0011 (as absolute addresses need 16-bit numbers). Remember the part under Registers and Ram where we mentioned using multiple memory locations? So here, we retrieve the number #$01 and #$02 from memory location $0010 and $0011 respectively. As 6502 is a little-endian processor, it stores the least significant byte (lower value) first. This means two byte data (like memory locations) store the least significant byte in the first memory address ($0010) and the most significant byte in the second address ($0011) . For example, the following hexadecimal number #$0201, the 01 is the least significant byte and 02 is the most significant byte. (Using a decimal example, 1030, the 30 which refers to thirty is smaller than the 10 which refers to one thousand.)

- Jump to this retrieved absolute location:

$0201

Here's another example:

At memory location $0040 there is the value #$03 and at memory location $0041there is the value #$02.

JMP ($0040)

What do you think this does?

Changes stack pointer and jumps to memory address

$0203.

Here, we:

- Retrieved the values at memory location

$0040and$0041to get the values$03and$02 - Since 6502 is a little-endia processor, the least significant byte (`$03`) is stored first and the most significant byte (`$02`) is stored lastso the retrieved memory adddress

$0203 - Change stack pointer and jump to memory address

$0203

A quick note: a flag, as mentioned above, is a special status register that tells the CPU something very specific about the current state. The z-flag is set by comparison instructions and tells us whether two things are equal (0 = not equal, 1 = equal) The ability to set conditions and loops is essential in being able to write programs and in assembly, here's how we can do this in assembly. First, we need to add something that tells us what needs to be looped. This can be indicated by a label.

label:

...

This is a label. We can think of it similarly as a function.

Next, we need something that can tell us whether to loop the section of the program. This is done in two parts:

- An instruction that tests a condition and sets a flag. This could be an instruction that compares such as

CPXmentioned above. - An instruction that checks the status of a flag and calls the label. Check out the full instruction set

In Javascript, a while loop that addings to variable x until it reaches 3 would look like this:

let x = 1

while(x < 3) {

x = x + 1

}

At the end of this program, the value of x is 3

LDX #$01

equalthree:

INX

CPX #$03

BNE equalthree

BRK

At the end of this program, the value at Register X is 3

Let's break this down:

LDX #$01: We load the number $01(=1) to Register XINX: We increment value in Register X by 1 (here value at Register X is#$02)CPX #$03: We compare value in Register X to#$03and it fails so the z-flag is set at 0BNE equalthree: We check if the z-flag is 0 and since it is still 0, we execute theequalthreelabel (BNE= Branch on Not Equal, execute label if values not equal). The next lineBRK(Break) is not called as we loop back to the labelequalthree.INX: We increment value of Register X by 1 (here value at Register X is#$03)CPX #$03: We compare value in Register X to#$03and it is true so the z-flag is set at 1BNE equalthree: We check if the z-flag is 0 and since it is now one, we DO NOT execute theequalthreelabelBRK: the program ends

Here's another example:

LDX #$04

equaltwo:

DEX

CPX #$02

BNE equaltwo

BRK

What will be the value at Register X after the program breaks? And can you walk through each step to show how you got there?

Here, we:

LDX #$04: We load the number $04(=4) to Register XDEX: We decrement value in Register X by 1 (here value at Register X is 3)CPX #$02: We compare value in Register X to#$02and it fails so the z-flag is set at 0BNE equaltwo: We check if the z-flag is 0 and since it is still 0, we execute theequaltwolabelDEX: We decrement value in Register X by 1 (here value at Register X is 2)CPX #$02: We compare value in Register X to#$02and it is true so the z-flag is set at 1BNE equaltwo: We check if the z-flag is 0 and since it is now 1, we DO NOT execute theequaltwolabel and we move to the next lineBRK: The program ends

Are you up for a challenge? Try writing your own loop here. Tip: Once you write your program, click Assemble and Run. Then, hit Reset, then check the Debugger checkbox to start the debugger. Click Step once and keep your eye on the Debugger box to see what changes as you run through the program.

Since languages such as Python and C allow us to do virtually the same thing in less time, people rarely code in Assembly beyond "why not?" so you most likely do not have an assembler or an actual computer with 6502 processor. However, fret not as @Esshahn open-sourced an easy to set up template to start coding in 6502, check it out here. The rest of this section is a summarised version of the instructions but if you're curious about the reasons behind each step, check out the repository.

Firstly, this setup requires that you code with Visual Studio Code so you will need to download VSCode.

Next, you need to dowload the Acme Cross Assembled (C64) Extension. This extension handles the assembly work of turning our assembly code into machine code that the machine can understand.

Check out the section on Communicating With the CPU if you're not sure what this means.

We also need a processor that actually understands the instructions given. We can get this by downloading Vice, an emulator which is basically a program that runs the way computers using the 6502 processor runs. Download the file that suits your computer (eg. I run on an Apple Silicon Mac so I chose the file under Apple Silicon Mac (macOS 11.0+)). After downloading, if you're on a Mac, you want to drag the folder into your applications folder. On other OS's, you might want to move the folder to the equivalent of an applications folder like tools in Windows.

Now, we need to download the git repository template here: https://github.com/Esshahn/acme-assembly-vscode-template. You can also directly downlod the file here.

A screenshot of where to download the repository

This file contains the binaries needed to assemble the language to machine code (check out the section on Communicating With the CPU) and also a tasks.json file which allows you to complete actions with VSCode, allowing you to send files to the VICE emulator.

Before we start assembling our program, we have one extremely important step! In the tasks.json file, there are different tasks for different emulators that you can download.

{

"label": "...",

...

}

Each of the code blocks above is one build task for an emulator (Vice has different options). Since we're coding in 6502, we'll pick C64 which we can call with the second task:

{

"label": "build -> C64 -> Pucrunch -> VICE",

"type": "shell",

"osx": {

"command": "bin/mac/acme -f cbm -l build/labels -o build/main.prg code/main.asm && bin/mac/pucrunch build/main.prg build/main.prg && /Applications/Vice/x64.app/Contents/MacOS/x64 -moncommands build/labels build/main.prg 2> /dev/null",

},

"windows": {

"command": "bin\\win\\acme -f cbm -l build/labels -o build/main.prg code/main.asm && bin\\win\\pucrunch build/main.prg build/main.prg && C:/tools/vice/x64.exe -moncommands build/labels build/main.prg",

},

"linux": {

"command": "bin/linux/acme -f cbm -l build/labels -o build/main.prg code/main.asm && bin/linux/pucrunch build/main.prg build/main.prg && x64 -moncommands build/labels build/main.prg 2> /dev/null"

},

"group": "build",

"presentation": {

"clear": true

},

"problemMatcher": {

"owner": "acme",

"fileLocation": ["relative", "${workspaceFolder}"],

"pattern": {

"regexp": "^(Error - File\\s+(.*), line (\\d+) (\\(Zone .*\\))?:\\s+(.*))$",

"file": 2,

"location": 3,

"message": 1

}

}

},

Depending on which operating system you use, a different line of code applies to you. Eg. if you use Mac, you only need to look at "osx": {...}. Within that, on the line with "command":, there is a small section that tells VS Code where your Vice Emulator is.

If you use a Mac, you need to swap out /Applications/Vice/x64.app/Contents/MacOS/x64 with the actual file path to where you stored your Vice so in this case it was in the Applications folder. DO NOT REMOVE Contents/MacOS/x64. You want to use x64sc so if you did indeed store your file in the Applications folder, your path should be /Applications/{folderName}/x64sc.app/Contents/MacOS/x64sc where {folderName}is the name of your folder, eg. vice-x86-64-gtk3-3.6.1.

If you use Windows, you need to swap out C:/tools/vice/x64.exe with the actual file path so if you stored it under tools, your file path should be C:/tools/{foldername}/x64sc.exe.

Finally the part where you code (yay!). You want to add your code to code/main.asm.

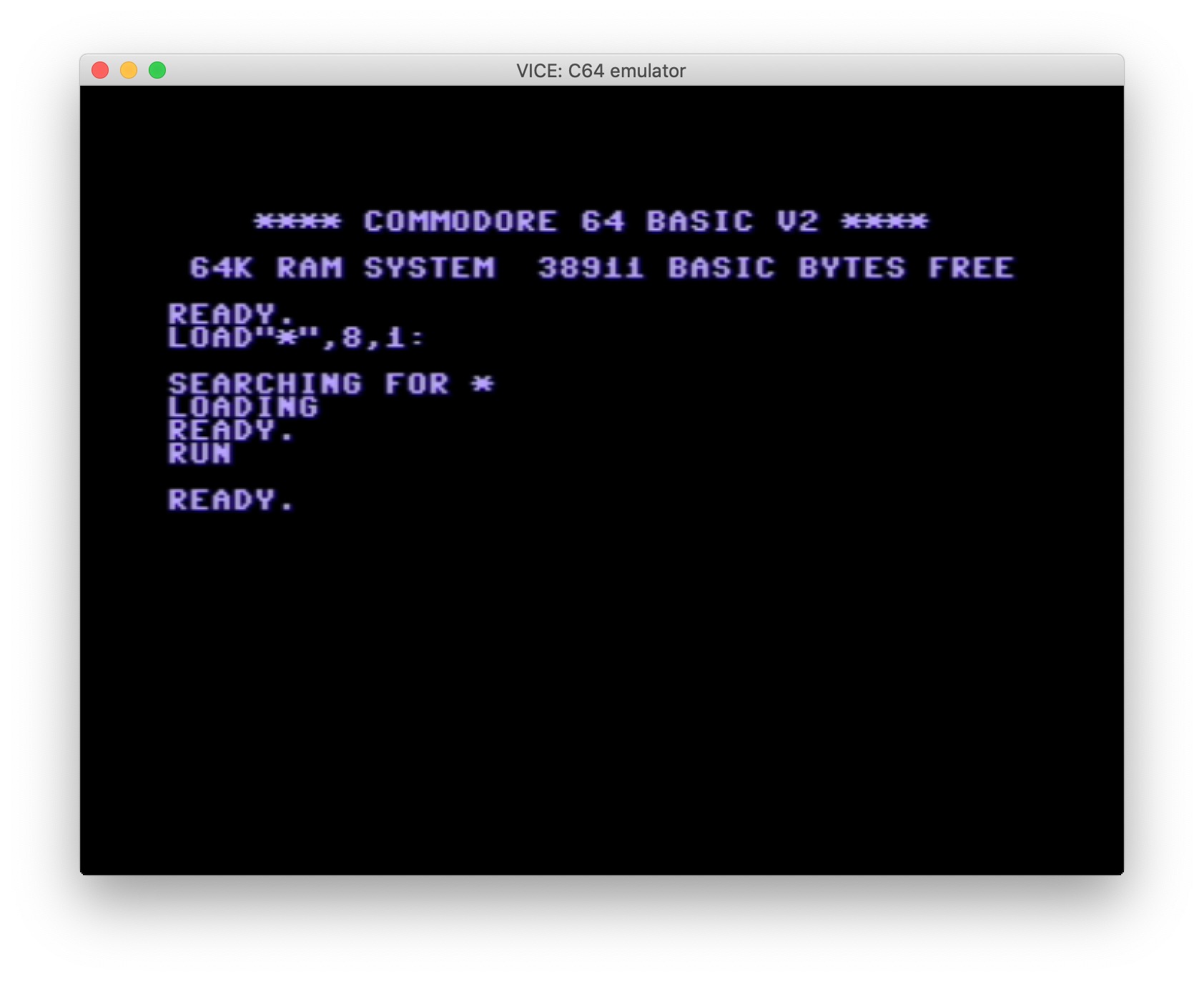

When you're done, to assemble the code, Press SHIFT + COMMAND + B (On Windows, it's SHIFT + CNTRL + B). If you're prompted by VSCode to select build task to run, pick build -> C64 -> Pucrunch -> VICE. It should open the VICE Emulator and look something like this:

Note: If it doesn't open the VICE Emulator but you don't see any errors in the terminal, open the build/main.prg (the binary executable) file directly with VICE. On Mac, you can do this by opening the file in terminal and right click to select open with > x64sc.

On Errors: If you see a failed to launch (exit code: 126) in the terminal, you might have missed /Contents/MacOS/x64sc and if you see failed to launch (exit code: 127) in the terminal, you're not pointing to the correct file location where your VICE Emulator is.

In response to the question above, the reason why it's only 2 digits is because a two digit hexadecial number can count up to 16*16 (256), which is the same as an 8 digit binary number which can count up to 2**8 (256). This is also known as a byte. Learn more about Number Systems here

Links that I found helpful when learning this 6502 Overview

- https://skilldrick.github.io/easy6502/ (easy to learn guide)

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yEiNs7pKNh8 (source for the introduction section)

- https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/6502_Assembly

- https://www.masswerk.at/6502/6502_instruction_set.htm (instruction set)

- https://codeburst.io/an-introduction-to-6502-assembly-and-low-level-programming-7c11fa6b9cb9

Other Code Examples