The C++ API documentation has an overview of usage and architecture and a discussion of drawbacks.

tsm is a state machine framework with support for Hierarchical and Orthogonal State Machines.

* Typed Hierarchical State machine.

* Simple memory model.

* Thread safe event queue.

* Single Threaded, Asynchronous, Periodic, Concurrent and real-time execution policies out of the box.

* Ease of installation and integration - Header only, CMake and Nix support.

* Policy Based - Ability to customize behavior by defining execution policies.

* Mostly Linux only. There is some freeRTOS support, but the status is unknown.

* C++17 required.

* std::variant is used.

struct SwitchContext {

// Events

struct Toggle {};

// States

struct Off {};

struct On {};

using transitions =

std::tuple<Transition<Off, Toggle, On>,

Transition<On, Toggle, Off>>;

};Clients can interact with this state machine in two ways - Synchronously and Asynchronously.

using SwitchSM = SingleThreadedHsm<SwitchContext>;

int main() {

SwitchSM s;

s.sendEvent(Toggle{});

s.step();

// ...

}using SwitchSM = ThreadedHsm<SwitchContext>;

int main() {

SwitchSM s;

s.start(); // Starts the state machine/event processing thread.

s.sendEvent(s.toggle);

// ...

s.stop(); // Shuts down the event processing thread.

}s.step() is missing in the ThreadedHsm. The State Machine thread blocks waiting for the next event to arrive in the event queue and processes it as soon as it arrives. So far, the "contract" is that the user creates a "Context" struct. When a policy is applied to it, the Context type is transformed into a state machine. The only must have requirement for a Context struct is that it must have a transitions type which defines the state transition table. The transition table is a std::tuple of Transitions.

Initial states are implied by the first "from" state in the first transition. There isn't support for stop states.

Every Hsm instance holds all the sub-states in a tuple. This tuple is initialized when the Hsm is instantiated. The current state is a variant holding a pointer to one of these states. Each Hsm also inherits from it's context type. So all data related to the context can be stored there and the Hsm class itself is unaware of the context's internals. When making call to the entry, exit and handle methods, the Hsm class will pass a reference to itself, but cast to the context type. This allows the Hsm to provide access the context's data. This allows the context to be a simple struct or a complex class with methods and data. If the context allocates any memory, it is the responsibility of the context to clean up all allocated memory in it's destructor. Declaring a virtual destructor guarantees that the context's destructor will be called when the Hsm is destroyed.

A whole class of problems can be solved in a much simpler manner with state machines that are driven by timers. Consider the problem of having to model traffic lights at a 2-way crossing. The states are G1(30s), Y1(5s), G2(60s), Y2(5s). When G1 or Y1 are on, the opposite R2 is on etc. The signal stays on for the amount of time indicated in parenthesis before moving on to the next. The added complication is that G2 has a walk signal. If the walk signal is pressed, G2 stays on for only 30s instead of 60s before transitioning to Y2. The trick is to realize that there is only one event for this state machine: The expiry of a timer at say, 1s granularity. Such problems can be modeled by using timer driven state machines. Applications include game engines where a refresh of the game state happens every so many milliseconds, robotics, embedded software and of course traffic lights :). This problem is modeled with a custom "handle" method without a state transition table and a LightState type inherited from the State struct.

To model a solution, we first implement the TrafficLight contexts. To reduce repetition in the transition table, Transitions are marked as ClockedTransitions. This is a very important pattern that abstracts away the notion of time. Now, coupled with a timer, we are able to drive a state machine at any Duration (1ms, 1s, 1us) or multiples for e.g. every 42ms. This makes testing easier as we can test the clocking separately from the state machine logic.

Summary so far. Contexts can have transitions. Implicit in that statement is that Contexts have to define States and Events. States can have entry, exit, guard and actions associated with them.

Below is a good start. From the description above, the state transitions are pretty clear. We've defined the states and a boolean that keeps track of the walk_pressed_ button.

namespace TrafficLight {

struct LightContext {

// States

struct G1 { };

struct Y1 { };

struct G2 { };

struct Y2 { };

bool walk_pressed_{};

using transitions =

std::tuple<ClockedTransition<G1, Y1>,

ClockedTransition<Y1, G2>,

ClockedTransition<G2, Y2>,

ClockedTransition<Y2, G1>>;

};Once we "start" the traffic light, G1 is not allowed to transition to Y1 until it has been on for 30s. A good candidate is a guard function. So we add a guard to G1 and modify the state transition table accordingly. Also, on exiting this state, Y1 will have to count to 5 and then transition to G2. So the tick count is reset. We add the guard and exit functions to G1

struct G1 {

void exit(LightContext&, ClockTickEvent& t) { t.ticks_ = 0; }

auto guard(LightContext& l, ClockTickEvent& t) -> bool {

if (t.ticks_ >= 30) {

return true;

}

return false;

};

// Alternately, you can combine exit, guard and action by providing your own handle method

struct G1 {

bool handle(LightContext&, ClockTickEvent& t) {

if (t.ticks_ >= 30) {

// exit action

t.ticks_ = 0;

return true;

}

return false;

}

};

Then modify the transition table to know about the guard (Note: This is not really necessary as the Hsm's handle method will look for an invocable guard method for the state).

std::tuple<ClockedTransition<G1, Y1, decltype(&G1::guard)>

or

std::tuple<ClockedTransition<G1, Y1>A more complete state context implementation will look like this. Look at the signatures of the exit and guard functions. Any information like walk_pressed_ is retained in the state context itself. The state machine itself is context agnostic and doesn't care about the context's implementation details.

namespace TrafficLightAG {

struct LightContext {

struct G1 {

void entry(LightContext&, ClockTickEvent& t) { t.ticks_ = 0; }

bool guard(LightContext&, ClockTickEvent& t) { return t.ticks_ >= 30; }

};

struct Y1 {

bool guard(LightContext&, ClockTickEvent& t) { return t.ticks_ >= 5; }

};

struct G2 {

void entry(LightContext&, ClockTickEvent& t) { t.ticks_ = 0; }

bool guard(LightContext& l, ClockTickEvent& t) {

return t.ticks_ >= 60 || (l.walk_pressed_ && t.ticks_ >= 30);

}

};

struct Y2 {

void entry(LightContext&, ClockTickEvent& t) { t.ticks_ = 0; }

bool guard(LightContext&, ClockTickEvent& t) { return t.ticks_ >= 5; }

boid action(LightContext& l, ClockTickEvent&) { l.walk_pressed_ = false; }

};

using transitions =

std::tuple<ClockedTransition<G1, Y1>,

ClockedTransition<Y1, G2>,

ClockedTransition<G2, Y2>,

ClockedTransition<Y2, G1>>;

// Note: context specific data

bool walk_pressed_{};

};

}An alternate way to implement this context is shown below:

namespace TrafficLight {

struct LightContext {

struct G1 {

bool handle(LightContext&, ClockTickEvent& t) {

if (t.ticks_ >= 30) {

// exit action

t.ticks_ = 0;

return true;

}

return false;

}

};

struct Y1 {

bool handle(LightContext&, ClockTickEvent& t) {

if (t.ticks_ >= 5) {

// exit action

t.ticks_ = 0;

return true;

}

return false;

}

void entry(LightContext& t) { t.walk_pressed_ = false; }

};

struct G2 {

bool handle(LightContext& l, ClockTickEvent& t) {

if (t.ticks_ >= 60 || (l.walk_pressed_ && t.ticks_ >= 30)) {

// exit action

t.ticks_ = 0;

return true;

}

return false;

}

};

struct Y2 {

bool handle(LightContext&, ClockTickEvent& t) {

if (t.ticks_ >= 5) {

// exit action

t.ticks_ = 0;

return true;

}

return false;

}

};

bool walk_pressed_{};

using transitions =

std::tuple<ClockedTransition<G1, Y1>,

ClockedTransition<Y1, G2>,

ClockedTransition<G2, Y2>,

ClockedTransition<Y2, G1>>;

};

} // namespace TrafficLightA namespace is used as an additional encapsulation mechanism. Now that there is a "simulated" model for this traffic light, we can drive it with a timer that "ticks" the state machine at a frequency of 1Hz. To turn this context into a periodic state machine,

#include <tsm.h>

using TrafficLightHsm = tsm::PeriodicHsm<LightContext,

PeriodicSleepTimer,

AccurateClock, // provided within TypedHsm.h

std::chrono::seconds>;... and voila! We have transformed the LightContext type by applying a policy that sends ticks at 1s intervals. Usage:

int main() {

TrafficLightHsm hsm;

hsm.start();

// ...

}hsm.start() will start a timer with a period of 1s. At the expiration of this timer, a ClockTickEvent will be placed in the event queue. After 30 such ticks are processed, the state machine will use the transition table information to perform the transition to Y1.

A couple more "contract"s to note. entry, exit, action and guards are named as such. You can optionally pass a reference to the context type. Having these methods within a state is also optional.

Context can be nested as "states" within a transition table. Let's say the TrafficLight has to transition to an "EmergencyMode".

struct EmergencyOverrideContext {

struct G1 {

void exit(EmergencyOverrideContext& t) { t.ticks_ = 0; }

auto guard(EmergencyOverrideContext& t) -> bool {

return t.ticks_ >= 5;

};

};

struct Y1 {

void exit(EmergencyOverrideContext& t) { t.ticks_ = 0; }

auto guard(EmergencyOverrideContext& t) -> bool {

return t.ticks_ >= 5;

};

};

struct G2 {

void exit(EmergencyOverrideContext& t) { t.ticks_ = 0; }

auto guard(EmergencyOverrideContext& t) -> bool {

return t.ticks_ >= 5;

};

};

struct Y2 {

void exit(EmergencyOverrideContext& t) { t.ticks_ = 0; }

auto guard(EmergencyOverrideContext& t) -> bool {

return t.ticks_ >= 5;

};

};

bool walk_pressed_{};

using transitions =

std::tuple<ClockedTransition<G1, Y1>,

ClockedTransition<Y1, G2>,

ClockedTransition<G2, Y2>,

ClockedTransition<Y2, G1>>;

};We've defined the contexts for emergency override above. Simply, it cycles through each state at 5s. Here is the TrafficLightHsmContext with two sub-contexts:

struct TrafficLightHsmContext {

// Events

struct EmergencySwitchOn {};

struct EmergencySwitchOff {};

using transitions = std::tuple<

Transition<LightContext, EmergencySwitchOn, EmergencyOverrideContext>,

Transition<EmergencyOverrideContext, EmergencySwitchOff, LightContext>>;

};We've added two events to transition to emergency mode and back to normal mode. To create a Hsm with two nested state machines, the application of policy classes is no different.

using LightHsm = ThreadedHsm<TrafficLight::LightContext>;

REQUIRE(std::holds_alternative<LightHsm*>(hsm.current_state_));

hsm.send_event(TrafficLight::TrafficLightHsmContext::EmergencySwitchOn());

REQUIRE(std::holds_alternative<TrafficLight::EmergencyOverrideContext::G1*>(

current_hsm->current_state_));For details see TestHsm.cpp.

Pushing the traffic light example a little farther:

namespace CityStreet {

struct Broadway {

// Traffic on Park Ave

using ParkAveLights = TrafficLight::LightContext;

// Traffic on 5th Ave - specialize if needed

using FifthAveLights = TrafficLight::LightContext;

using type = make_orthogonal_hsm_t<ParkAveLights, FifthAveLights>;

};

}The same example above can be turned into a concurrent state machine when instantiated with:

using type = make_concurrent_hsm_t<ClockedHsm, ParkAveLights, FifthAveLights>;Policy classes are provided for several scenarios. Threaded (Asynchronous), Single threaded, Periodic, Real-time and concurrent execution. You can combine policies like this:

template <typename T>

using ThreadedClockedHsm = ThreadedExecutionPolicy<ClockedHsm<T>>;

// Both ParkAveLights and FifthAveLights can be `tick`-ed. ie. they own their own clocks and operate

// concurrently.

using type = make_concurrent_hsm_t<ThreadedClockedHsm, ParkAveLights, FifthAveLights>;Here is an excerpt from tsm.h for a more complicated policy class:

/// Real-time state machine. This state machine is driven by a periodic timer.

/// E.g.

template<typename Context>

using MyRealtimePeriodic1KhzPolicy =

RealtimePeriodicExecutionPolicy<Context,

RealtimeExecutionPolicy,

PeriodicTimer<std::chrono::steady_clock, std::chrono::milliseconds>>;

using MyRealtimePeriodic1KhzHsm = MyRealtimePeriodic1KhzPolicy<MyEtherCATContext>;

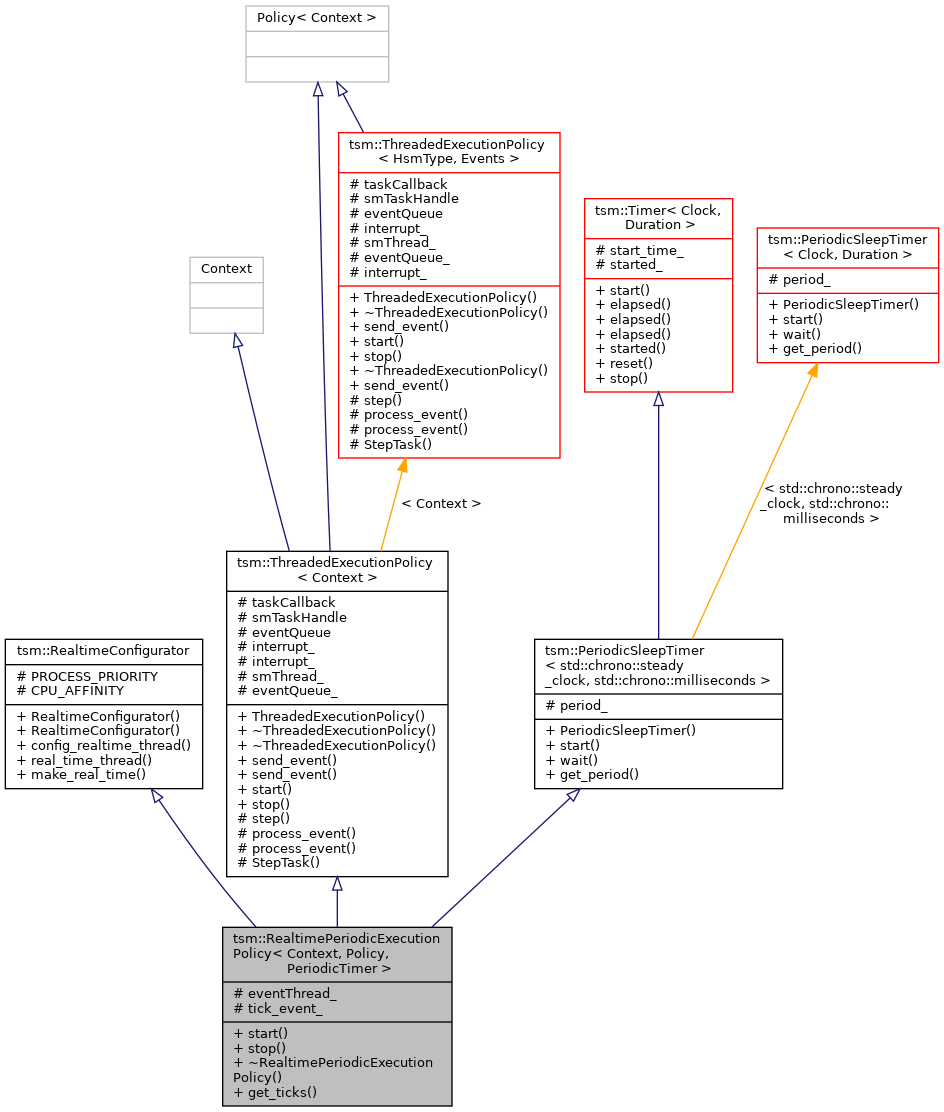

MyRealtimePeriodic1KhzHsm sm;Here is it's inheritance graph:

Like it? Try it.

If you don't want to install nix, sudo apt install cmake ninja-build graphviz doxygen or brew install cmake ninja graphviz doxygen. Read the CMakeLists.txt to get a good feel for it. The cmake/superbuild folder contains the cmake files that download and install the external dependencies. With Nix, none of these cmake files are needed. The dependencies and environment will be set up when you invoke nix-shell or nix-build.

git clone https://github.com/tinverse/tsm.git

cd tsm; mkdir build; cd build

# cmake .. && make #if you want to use make

cmake -GNinja -DCMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX=${HOME}/usr .. && ninja install

# run tests

./bin/tsm_testHow do I use it from my project? Look at the example project CMakeLists.txt. Use this as a template for your project's CMakeLists.txt. The tsm_DIR variable should be set to point to the location of tsmConfig.cmake (for the case above, ${HOME}/usr/lib/cmake/tsm).

Install nix by running curl https://nixos.org/nix/install | sh. The default.nix file is responsible for setting up your environment and installing all required dependencies.

nix-shell --run ./build.shAnd you are done! If you open build.sh you'll notice that it uses ninja instead of make. build.sh creates a build folder, invokes cmake to generate the build scripts and then calls ninja or make via the cmake --build command to create the build outputs. You can find the test executable tsm_test under build/test, documentation under build/docs/html and coverage data under test/tsm_test-coverage. For your normal workflow,

nix-shell

cd build

ninja tsm_testYou can also run nix-build from the command-line. This will build all targets and deploy them to /nix/store. A sym-link named result will be created in the cloned folder (the folder that contains default.nix) to the /nix/store. So to invoke tsm_test, run ./result/test/tsm_test.

If making changes to tsm source, you can generate coverage reports as well. The cmake option -DBUILD_COVERAGE=ON turns it on. Feel free to steal this mechanism for your own projects. ninja coverage will invoke lcov and the report will be available under test/tsm_test-coverage/index.html in the build folder.

To generate doxygen docs, use the cmake option -DBUILD_DOCUMENTATION=ON. This can be invoked as needed - ninja tsm_doc or just plain ninja from the build folder.

None, if you just want to use the library. Just #include <tsm> and start using it! Catch2 unit test framework if you wish to run the unit tests. Set BUILD_TESTING=OFF in the CMakeCache file to disable building unit tests.

Please feel free to write up issues and submit pull requests. There is a .clang-format file that comes with the source. Coding conventions can be inferred by looking at other source files.

* UML front end to define State Machine.