Git is a version control software (VCS) that has become the standard for managing development projects. It serves two main purposes:

- Version Control: manage the evolution of a project as it grows in complexity, easily rollback or revert breaking changes, inspect history, and maintain separate versions for development, integration, release, etc.

- Collaboration: allow many users to collaborate on a single codebase remotely in an effective and managed manner; provides tools for integrating changes from multiple developers, resolving conflicts, and tracking the owner of certain features/changes.

- You should use git for every software project you work on, regardless of whether you share that project with others.

- You do not need to use GitHub with git.

- You should be comfortable with using git from the command line (without a GUI).

- You do not need to memorize all the git commands, but we'll cover an important set of them.

- You do not need to be a pro on resolving merge conflicts, but should be comfortable if one pops up.

Note: git keeps track of all this neat stuff in a folder that you can view (put should probably never mess with) in the projects

.git/folder

We'll cover the core concepts and terms that are fundamental to understanding git

- Repository: A "repo" is a collection of managed code. It may represent a complete project, a part of a larger project, or really logical unit of code.

- Remote: Repositories can be set up to keep in sync with a "remote" repository that is kept in a central place like GitHub, GitLab, BitBucket, etc. allowing for effective collaboration.

- Branch: A branch is a tool to keep some collection of changes separated from the rest of the project. Commonly used to work on developing new features while the "main" branch is kept stable.

- Commit: A commit marks a set of changes submitted to the code's history. It's up to the developer to decide what should go in a commit, but best practice is to keep commits small and "atomic", meaning that they can stepped through one-by-one without breaking the project. These are identified by a "SHA" (unique hash value).

- HEAD: This is a special marker in git (similar to a "SHA") that points to the latest commit on the active branch (indicating where new commits will be applied).

- Working Tree: This represents the state of the files on your local computer. This may include new changes, ignored files, etc. and thus not fully match the state of the repository.

- Stage: The stage is the collection of changes that are about to be committed. This allows you to specify which changes make it into a commit when you have a lot of unrelated changes in your working tree.

- config

- gitignore

- global gitignore

For more information and suggestions of initial configuration of your git client, see the official git docs

$ git config --global user.name "John Doe"

$ git config --global user.email johndoe@example.com

$ git config --global init.defaultBranch main

$ git config --global core.editor nano # (OPTIONAL; will use nano instead of vim)

$ git config --global core.excludesfile ~/.gitignore_global

$ nano ~/.gitignore_global. # See below for global gitignore suggestions

$ git config --list

user.email=johndoe@example.com

user.name=John Doe~/.gitignore_global

.DS_Store

.vscode/

.idea/

__pycache__/

*.egg-info/

.env

.venv

env/

venv/

Local repositories can be kept in sync with a single "remote" (git calls this origin by default), or with many named remotes. Each remote will have an identifying name and a url associating it with the remote repository.

A "remote" is just a central location for a repository to be kept, allowing for local repositories to keep in sync with each other. You may wish to use a remote for collaboration, or just as a backup place for your personal projects to live. GitHub, GitLab, and BitBucket are all popular choices. Users interact with remotes via push and pull to publish local changes and retrieve changes contributed by others.

A "fork" is just a way for you to contribute or make changes to another remote repository without direct collaboration. Many open source projects have strict guidelines or restrictions around who can contribute code and how. If you find you need to make changes to a repository you don't own, remotes give the option to create a fork which retains a link to the source but grants ownership to you. Forks operate like branches but at a higher level.

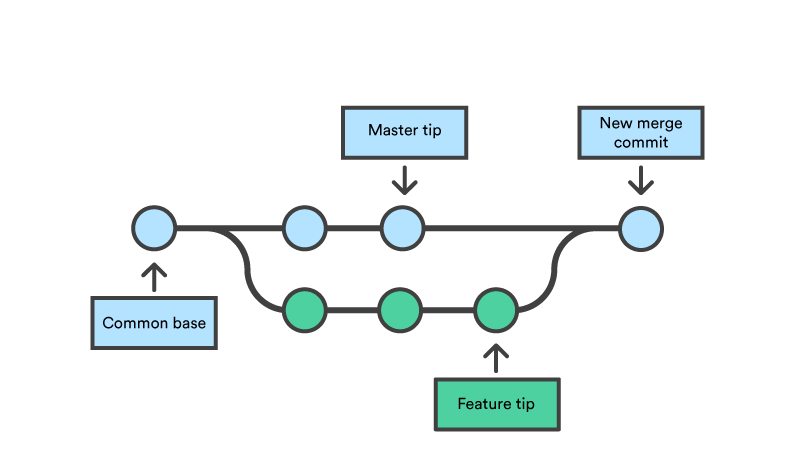

When you interact with a remote repository with many collaborators, you are bound to encounter conflicts when attempting to reconcile (merge) changes made by multiple people.

For example, you may change a script to load a file from you computer's local filesystem; one of your collaborators do the same. When you both push to the same central remote, the remote will see two different changes to the same line of code and panic; you must tell git how to "resolve" that conflict. There are lots of ways to avoid or reduce merge conflicts (and lots of ways to resolve them), but that's a bit beyond scope of this tutorial. In general, try to communicate with and separate your work from your collaborators, use branches, pull requests, and other provided tools, and keep system-specific configuration in environment variables or an "ignored" configuration file (kept out of version control).

Pull requests are a feature provided by remotes (like GitHub, etc.) which offer a nice way to integrate changes which have been kept in separate branches. Most common is a request to merge development changes back into the "main" branch once deemed complete. Typical pull request systems allow you to specify the source and destination branches (e.g. development -> main), provide comments on your request, solicit reviews from collaborators, review code changes and submit comments or approval/request to change, and finally merge the changes from source to destination branch. Pull requests are an excellent feature as they help keep the main branch clean and give collaborators a place to review and discuss each other's work.

Git is pretty flexible and leaves a lot of room for style and choice. However, because git is meant to simplify collaboration, it is worth following some common best practices if you can.

- Test first, commit second: commits become a part of the project's permanent history, try not to commit things that are broken.

- Use your stash for unfinished work: if you need to pull, or checkout something but have in-progress, local changes, you can "stash" them instead of creating a temporary commit.

- Commit early and often: repo timelines are far more helpful if you can step through small, incremental changes.

- Write good messages: more info below.

- Don't panic: if you think you've messed up, don't worry - so has everyone - and there are lots of guides online! Just a simple google of "Oops... I committed all those changes to the master branch" will usually get you an answer!

Motivation: As noted, commits are meant to be stable checkpoints in history containing some small, meaningful change and able to run stably on its own. Because of this, a commit needs to help you identify what that change was and why it's there! The contents of a commit can be easily inspected to show what changed; however, the "why" is answered only by the commit message. Make a point to answer this question in your commit message.

Format:

Title should answer the prompt: "If applied, this commit will..."

Allow users to log in with one time passcode

Body should provide more detail around the motivation.

Project managers have requested TFA for increased security. Users have indicated a hesitance to install additional apps for this so we decided on OTP for convenience.

Example:

Capitalized, short (50 chars or less) summary

More detailed explanatory text, if necessary. Wrap it to about 72

characters or so. In some contexts, the first line is treated as the

subject of an email and the rest of the text as the body. The blank

line separating the summary from the body is critical (unless you omit

the body entirely); tools like rebase can get confused if you run the

two together.

Write your commit message in the imperative: "Fix bug" and not "Fixed bug"

or "Fixes bug." This convention matches up with commit messages generated

by commands like git merge and git revert.

Further paragraphs come after blank lines.

- Bullet points are okay, too

- Typically a hyphen or asterisk is used for the bullet, followed by a

single space, with blank lines in between, but conventions vary here

- Use a hanging indent

If you use an issue tracker, add a reference(s) to them at the bottom,

like so:

Resolves: #123

The seven rules of a great Git commit message (from Chris Beams blog)

- Separate subject from body with a blank line

- Limit the subject line to 50 characters

- Capitalize the subject line

- Do not end the subject line with a period

- Use the imperative mood in the subject line

- Wrap the body at 72 characters

- Use the body to explain what and why vs. how

A few basic rules to keep in mind:

- Try to avoid working on the same file in the same branch as another developer as this will inevitably lead to merge conflicts.

- If you are working on the same branch as a collaborator, communicate well and pull/push often so that they know what you've changed and are not stuck waiting on un-pushed changes while you're away.

- You should (almost) never rewrite history in the remote. If you need to "undo" some commits locally, that's fine. But don't undo commits that have been pushed as this will corrupt repo history for people who have pulled recently. Instead, use

git revert <SHA>which will create a new commit undoing the specified changes.

There are many different workflows for collaboration - pick your favorite for your own projects, or check with your team/project owners for there preferred strategy.

Note: most open source projects include a

COLLABORATING.mddocument outlining their desired collaboration pattern. Please respect this if you plan to contribute!

status: Shows the current status including current branch, comparison to remote, list of new changes, and the stage contents ready for commitlog: Shows a log of commits made on the current branchshow: Shows the changes contained by a particular commit (or other git object)diff: Shows the changes between particular commits or between a commit and the working treestash: Moves your current set of changes into a "stash" for later, returning your working tree to the last commit (can thenlist,apply, orpopthem back out)add: Adds changes from working tree to the "stage"reset: Removes changes from the "stage" (changes kept in working tree)commit: Commits the changes in "stage" to version control historyrevert: Create a new commit (or commits) that undo the specified changesbranch: List (-l,-r,-a, or with no arguments), create (specify branch name as argument), or delete branches (-dor-D)checkout: Switch branches or restore some file in working tree from its state in history (git checkout -- some_file)tag: Create a new tag pointing toHEADor list existing tags, or delete a specified tag

clone: Download some repository from a remote to your local machine (must have access if private)fetch: Download objects and refs (branches/tags) from remoteremote: Manage remote repositories tracked by local repository (no arguments to list remotes,-vto include associated urls)addto add new remote (specify name and url)renameto change name for existing remoteremoteto removeset-urlto change url for existing remote

pull: Incorporate remote changes to local branch (fetchandmergeby default); this will make changes to your working tree (local filesystem)merge: Creates a new commit which includes all the changes from two branches since their divergencerebase: Reapply commits on top of another base (stashes your un-pushed local commits, pulls down the new remote commits, then pops those stashed local commits)

Note: merge and rebase can be quite confusing... I think this guide explains the difference quite well; or, more info on merge and rebase

Note: anything that changes your working tree (pull, merge, rebase, etc.) should only be run with a clean working tree; e.g. stash or commit any new changes first.

Tags are useful references that point to a particular reference (commit/branch). This allows you to identify commit 2f8b5e9ccef3d9ac0d03db8f5187124e33d400dd as tag `v1.0 - much nicer! Tags end up being used to identify significant development points, most often: versions.

Remotes typically allow you to create a "release" with documentation, packaged software, and the source code associated with a particular point in the repository's history. These are particular useful when managing software used by others.

Wikis provide a place for you to add extra documentation (typically much more extensive than a README file) for your users. This may be geared towards using the actual software provided by your project, explaining the history of the project, or anything else you deem important.

On one side, issues allow users to report bugs, request new features, or open discussions. On the other side, Issues provide developers and project maintainers a way to track milestones and tasks, interact with collaborators prior to development, and triage priorities. Many open source projects include Issue Templates that specify what content users should include in new features.

Remote repositories allow you to control settings such as access controls, integrations, branch protection and much more.

GitHub allows you to clone repositories via an https link specific to the repo. This requires that you submit your username/password to authenticate the request. A more secure (and much more convenient) way to do this is via ssh keys - the same keys we use to authenticate to servers and uploaded to our own GitHub accounts in the the ssh tutorial. Similarly, you can create "deployment keys" for use on an application server. This single-use key must be unique across all repositories in your account and can be used to grant a server read-only or read/write access to a single repository.

You can try this with any repository you have access to, for now, let's try it with this one (since it's public).

On the repository home page, you should see a big green button that says Code. Just click this button to clone it - but wait! If you're new to ssh, your pop-up probably says HTTPS at the top - we want to change that to SSH. The new link to copy should look like: git@github.com:michaelfedell/linux_essentials.git

GPG Keys as a construct are beyond scope of this tutorial, but in short, they allow you to verify your identity publicly so that collaborators can be confident that some commit with your username attached did in fact come from you. Anyone can actually make unsigned commits using your email address/username; signing them with a GPG key that you own is a way to protect your identity. See More

Actions were introduced to GitHub fairly recently and allow users to perform CI/CD operations on GitHub's shared resources. CI/CD is beyond the scope of this tutorial, but we can discuss GH Actions in more detail if you're interested. See More

GitHub Pages provide a super simple way to publish a website for yourself based on a GitHub repository. This can be done in just a few simple clicks and is a great way to show off your projects, host a personal portfolio page, or provide more documentation for a public project. We don't have time to cover this in depth today, but can go over it another time if you're interested. See More

Have made a ton of changes since my last commit...

add/commit changes incrementally

Can't pull because I've made changes...

stash/commit first!

Can't push because someone else has made changes...

stash/commit first, then pull (merge/rebase), then push

Can't find the changes I was working on...

check your stash, check your current branch, etc.

Need to "go back in time"...

git checkout ; warning: this will "detach" you from the current, what you do from here is up to you

Mess up some file and need to reset it

git checkout -- ; warning: this will discard your current changes and restore file to it's last committed state

Forgot to add a file to my last commit

git commit --amend --no-edit (I use

oopsfor this); warning: this modifies history and should not be done to commits already pushed to remote

Accidentally committed something secret (api key, passwords, etc...)

It's in history forever...

Expire the secret (at least), if it doesn't matter, you could delete the remote repository and create a new repository with all the content but none of the history (rm -rf ./.git; git init), or if you need to keep the history, you can purge your secrets with a tool called bfg; if you need to do this, you probably need to pull up a much more complete guid,

Committed something that shouldn't be in git (not sensitive)

git reset or git remove --cached

Have made a ton of commits on my branch that I don't want to show up in main branch

git rebase --interactive

Or, just check out this great blog on How to undo (almost) anything with Git.

GitHub provides a nice "cheat sheet" for common git commands:

https://education.github.com/git-cheat-sheet-education.pdf

Atlassian (providers of BitBucket) has an excellent tutorial/handbook for all things git:

https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/what-is-version-control

https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/setting-up-a-repository

git-scm is the official git software website, their manual pages are often quite helpful when googling something specific, or you can see there handbook here:

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Getting-Started-About-Version-Control